Lesson 175:

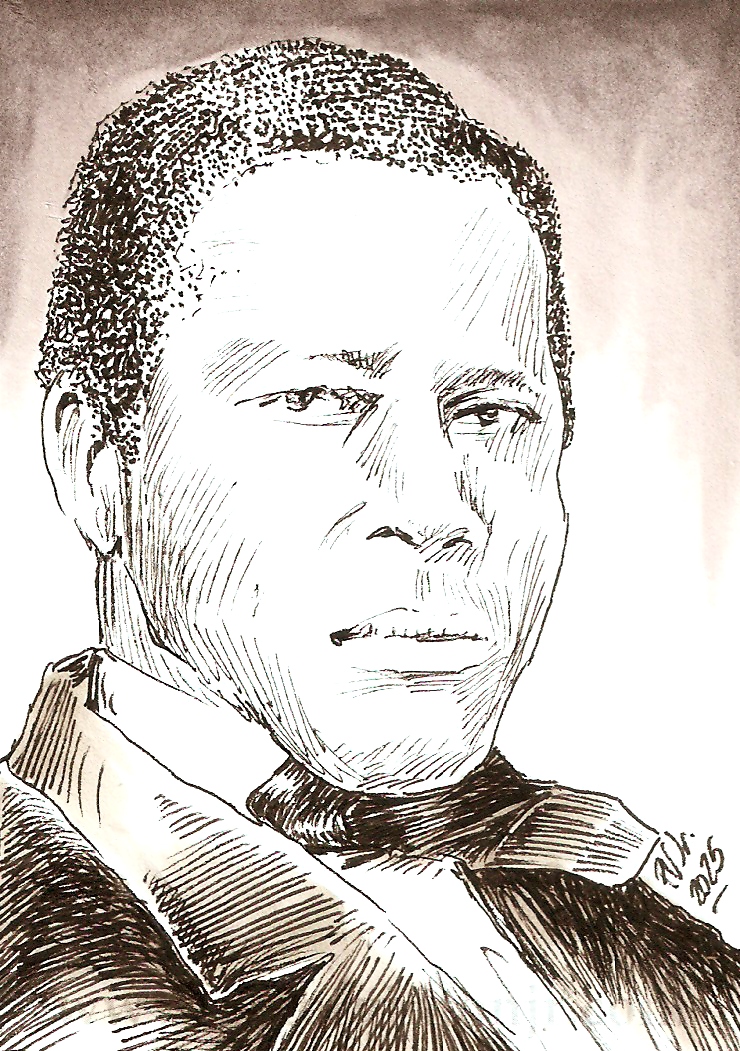

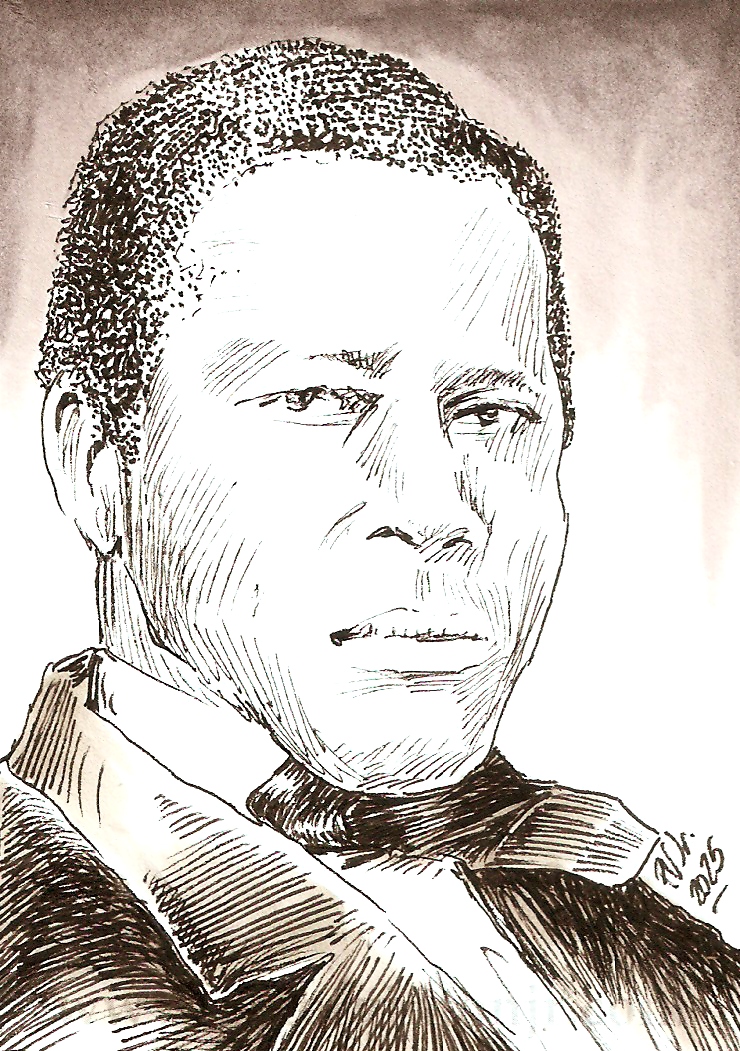

William Still

An ongoing illustrative history study

This piece originally posted on 02/24/2025

Today we'll delve into the life and the mostly-behind-the-scenes accomplishments of abolitionist William Still. Born in 1819 to formerly-enslaved parents who had managed to escape to New Jersey, William was the youngest of eighteen siblings. However his two eldest brothers, by dint of conflicting state law fineprint of the time, were themselves still considered legally enslaved in Maryland, and were then sold to plantation owners in Kentucky, and then to Alabama --putting them beyond the reach of the rest of their family. The oldest brother, Levin, died of whipping injuries, but the second brother, Peter, eventually managed to escape to Ohio at the age of 50 with his wife and their family; Peter would later publish a memoir of the experience in 1856. Peter would eventually reunite with his brother William after having been separated for 42 years, thanks in part to the assistance of The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society: an organization that actively helped escaped slaves, and was in many ways model/forerunner for the Underground Railroad.

Today we'll delve into the life and the mostly-behind-the-scenes accomplishments of abolitionist William Still. Born in 1819 to formerly-enslaved parents who had managed to escape to New Jersey, William was the youngest of eighteen siblings. However his two eldest brothers, by dint of conflicting state law fineprint of the time, were themselves still considered legally enslaved in Maryland, and were then sold to plantation owners in Kentucky, and then to Alabama --putting them beyond the reach of the rest of their family. The oldest brother, Levin, died of whipping injuries, but the second brother, Peter, eventually managed to escape to Ohio at the age of 50 with his wife and their family; Peter would later publish a memoir of the experience in 1856. Peter would eventually reunite with his brother William after having been separated for 42 years, thanks in part to the assistance of The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society: an organization that actively helped escaped slaves, and was in many ways model/forerunner for the Underground Railroad.

With such a heartbreaking family history and vivid personal firsthand experience, it was probably inevitable that William Still would quickly rally to the cause of abolition. In 1844 he moved to Philadelphia and joined the aforementioned Society, originally as a clerk and then ultimately as its chairman --the first Black man to do so. In 1847 he married Letitia George; together they assisted with helping a great many escaped slaves into Northern states or even into Canada --at one point averaging 60 runaways per month. Two of these 'adventures' (for lack of a more appropriate word) gained considerable notice in the popular press: Jane Johnson and her two sons, who escaped from an owner in 1855 (said owner later sued Still but lost); and Lear Green, who was famously smuggled into New York in a sailor's chest in 1850. The Stills were also instrumental in sheltering several of John Brown's co-conspirators after the failed 1859 raid at Harper's Ferry (see Lesson #116 in this series for more about that singular event). During the Civil War Still oversaw the postal exchange at Camp William Penn, a training ground in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania for United States Colored Troops (USCT).

Over the years Still kept meticulous records of his and Letitia's efforts to rescue and shelter fugitive slaves, and their many connections to their fellow "conductors" and agents --both in the South, and as far north as Canada. While anecdotally there is no indication that they ever met or interacted with Harriet Tubman, they were very much contemporaries and certainly would have moved in much the same circles. After the Civil War, Still remained fiercely devoted to the cause of civil rights, and managed several businesses and philanthropic organizations, to include Philadelphia's first YMCA. In 1867 he published Struggle for the Civil Rights of the Coloured People of Philadelphia in the City Railway Cars, a narrative of Still's campaign to end Black exclusion from city streetcars. Later in 1871 he published The Underground Railroad Records, a definitive memoir that is today regarded as one of the fundamental publications that provides proper context of the time, containing many firsthand testimonials from people like Lear Green and Jane Johnson, and also from other Underground Railroad conductors. Still died in 1902 and is buried at Eden Cemetery, now the nation's oldest African-American owned cemetery.

For further study:

PBS's Underground Railroad: The William Still Story. (Approx. 55 minutes, originally aired Feb 5, 2012)

Next lesson - Lesson 176: Annie Easley

Return to www.petervintonjr.com Main Page

Today we'll delve into the life and the mostly-behind-the-scenes accomplishments of abolitionist William Still. Born in 1819 to formerly-enslaved parents who had managed to escape to New Jersey, William was the youngest of eighteen siblings. However his two eldest brothers, by dint of conflicting state law fineprint of the time, were themselves still considered legally enslaved in Maryland, and were then sold to plantation owners in Kentucky, and then to Alabama --putting them beyond the reach of the rest of their family. The oldest brother, Levin, died of whipping injuries, but the second brother, Peter, eventually managed to escape to Ohio at the age of 50 with his wife and their family; Peter would later publish a memoir of the experience in 1856. Peter would eventually reunite with his brother William after having been separated for 42 years, thanks in part to the assistance of The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society: an organization that actively helped escaped slaves, and was in many ways model/forerunner for the Underground Railroad.

Today we'll delve into the life and the mostly-behind-the-scenes accomplishments of abolitionist William Still. Born in 1819 to formerly-enslaved parents who had managed to escape to New Jersey, William was the youngest of eighteen siblings. However his two eldest brothers, by dint of conflicting state law fineprint of the time, were themselves still considered legally enslaved in Maryland, and were then sold to plantation owners in Kentucky, and then to Alabama --putting them beyond the reach of the rest of their family. The oldest brother, Levin, died of whipping injuries, but the second brother, Peter, eventually managed to escape to Ohio at the age of 50 with his wife and their family; Peter would later publish a memoir of the experience in 1856. Peter would eventually reunite with his brother William after having been separated for 42 years, thanks in part to the assistance of The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society: an organization that actively helped escaped slaves, and was in many ways model/forerunner for the Underground Railroad.