Lesson 197:

James Armistead Lafayette

An ongoing illustrative history study

This piece originally posted on 08/06/2025

I figure we may as well keep going with the established mid-1770's theme, inasmuch as it is possible to do so. In the previous lesson we touched on Black Loyalists and their oft-overlooked role during the American Revolution; for this entry we'll upend that very subject, with a look at the life of James Armistead (later Lafayette). Born enslaved in 1760 Virginia, James Armistead actually enlisted into the Continental Army in 1781 (with the consent of his then-owner). Of all the luminaries to which he could have been attached, it transpired that James was detailed to a unit under no less than the Marquis de Lafayette himself. While the details of the conversations are not recorded, at some point Lafayette persuaded James to work as a spy; his cover would be to pose as a runaway slave who had been hired by the British to spy on the Americans. (Which wouldn't have been the slightest bit unusual!)

I figure we may as well keep going with the established mid-1770's theme, inasmuch as it is possible to do so. In the previous lesson we touched on Black Loyalists and their oft-overlooked role during the American Revolution; for this entry we'll upend that very subject, with a look at the life of James Armistead (later Lafayette). Born enslaved in 1760 Virginia, James Armistead actually enlisted into the Continental Army in 1781 (with the consent of his then-owner). Of all the luminaries to which he could have been attached, it transpired that James was detailed to a unit under no less than the Marquis de Lafayette himself. While the details of the conversations are not recorded, at some point Lafayette persuaded James to work as a spy; his cover would be to pose as a runaway slave who had been hired by the British to spy on the Americans. (Which wouldn't have been the slightest bit unusual!)

During his time in this dangerous dual role, James gained the confidence of British General Charles Cornwallis; to the point where Cornwallis entrusted James to guide British troops through local roads and thoroughfares. James overheard many conversations amongst the British officers, many of whom who had no compunction about openly boasting about their plans in his presence. James surreptitiously handed off his written notes to other American spies and remained undercover in Cornwallis's camp for nearly two years. While there were other spies operating in Cornwallis's purview, none were able to deliver nearly as much tactical intelligence as James --a detail that was even noticed by Gen. George Washington. James's last field report of July 31, 1781 helped Lafayette trap the British at Hampton, which is widely accepted as the lead-in to the eventual British surrender at Yorktown.

After the war Lafayette had made a point of publicly praising James Armistead for his bravery and dedication, but he had already returned to his life as a slave as, due to fine-print quibbles, was not eligible for emancipation as he had not technically served as a soldier. To his credit Lafayette spent the next two years seeking out information on Armistead, and finally found him in 1784. Disappointed to learn James had returned to enslavement, Lafayette again spoke out on his behalf, this time directly to the Virginia General Assembly, who eventually emancipated him --a full two years later. Armistead took on the surname Lafayette and moved to New Kent County, where he was not only able to collect a postwar pension, but to eventually obtained 40 acres of farmland and raised a family. He died at home in 1832, at the remarkable age of 72.

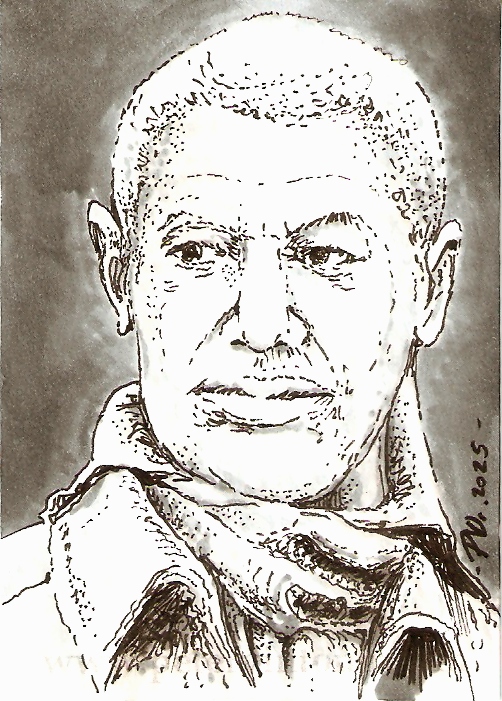

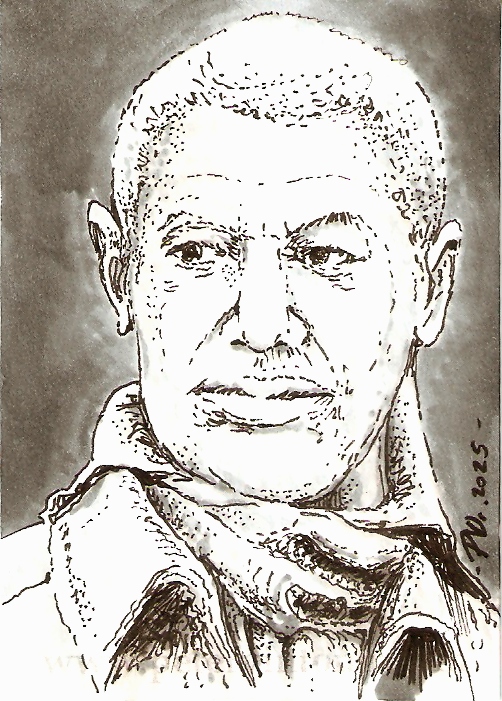

In support of this lesson, for James's likeness I am drawing upon a remarkable sculpture by Kinzey Branham of the University of Georgia, rather than the very few poor (and insultingly stereotypical) depictions offered by history.

Next lesson - Lesson 198: Boston King

Return to www.petervintonjr.com Main Page

I figure we may as well keep going with the established mid-1770's theme, inasmuch as it is possible to do so. In the previous lesson we touched on Black Loyalists and their oft-overlooked role during the American Revolution; for this entry we'll upend that very subject, with a look at the life of James Armistead (later Lafayette). Born enslaved in 1760 Virginia, James Armistead actually enlisted into the Continental Army in 1781 (with the consent of his then-owner). Of all the luminaries to which he could have been attached, it transpired that James was detailed to a unit under no less than the Marquis de Lafayette himself. While the details of the conversations are not recorded, at some point Lafayette persuaded James to work as a spy; his cover would be to pose as a runaway slave who had been hired by the British to spy on the Americans. (Which wouldn't have been the slightest bit unusual!)

I figure we may as well keep going with the established mid-1770's theme, inasmuch as it is possible to do so. In the previous lesson we touched on Black Loyalists and their oft-overlooked role during the American Revolution; for this entry we'll upend that very subject, with a look at the life of James Armistead (later Lafayette). Born enslaved in 1760 Virginia, James Armistead actually enlisted into the Continental Army in 1781 (with the consent of his then-owner). Of all the luminaries to which he could have been attached, it transpired that James was detailed to a unit under no less than the Marquis de Lafayette himself. While the details of the conversations are not recorded, at some point Lafayette persuaded James to work as a spy; his cover would be to pose as a runaway slave who had been hired by the British to spy on the Americans. (Which wouldn't have been the slightest bit unusual!)