Lesson 198:

Boston King

An ongoing illustrative history study

This piece originally posted on 08/16/2025

Now let's talk about an actual Black Loyalist. Meet Boston King, born enslaved in (or around) 1760 in South Carolina. Significantly, King's parents were first-generation slaves (meaning, kidnapped and brought over from Africa). Both were literate and ensured that their son would also become so. Ostensibly apprenticed as a carpenter, as King would later tell it, his particular owner was so harsh and cruel with his punishments (floggings) that one instance left him unable to work for three weeks. During the Revolution, King stole ("borrowed") a horse and slipped away from his owner, pledging loyalty to the British near Charleston, undertaking dangerous missions on behalf of Captain Grey of the New York Volunteers, which was a Loyalist regiment from Nova Scotia. King later made his way to New York --the last American port to be evacuated by the British-- and while there he met Violet, another former South Carolina slave who had also joined the British side with the promise of freedom. After the Revolution, Boston and Violet were given certificates of freedom for their service to the British crown. Along with nearly 3,000 other Black Loyalists who had risked severe punishment and even execution during the war, they were evacuated and resettled in British-held Birchtown, Nova Scotia.

Now let's talk about an actual Black Loyalist. Meet Boston King, born enslaved in (or around) 1760 in South Carolina. Significantly, King's parents were first-generation slaves (meaning, kidnapped and brought over from Africa). Both were literate and ensured that their son would also become so. Ostensibly apprenticed as a carpenter, as King would later tell it, his particular owner was so harsh and cruel with his punishments (floggings) that one instance left him unable to work for three weeks. During the Revolution, King stole ("borrowed") a horse and slipped away from his owner, pledging loyalty to the British near Charleston, undertaking dangerous missions on behalf of Captain Grey of the New York Volunteers, which was a Loyalist regiment from Nova Scotia. King later made his way to New York --the last American port to be evacuated by the British-- and while there he met Violet, another former South Carolina slave who had also joined the British side with the promise of freedom. After the Revolution, Boston and Violet were given certificates of freedom for their service to the British crown. Along with nearly 3,000 other Black Loyalists who had risked severe punishment and even execution during the war, they were evacuated and resettled in British-held Birchtown, Nova Scotia.

(This was neither a smooth nor a guaranteed process --Gen. George Washington had been negotiating firmly with the outgoing British commander-in-chief over the fate of Loyalist slave refugees, perhaps mindful of the vulnerability of his own "assets." [See Lesson #123 in this series!] Persistent eleventh-hour rumours that negotiations might fail and that the former slaves might yet be deported back to their former owners brought considerable anxiety; in King's words, "For days, we lost our appetite for food and sleep departed from our eyes.")

Now married to Violet and resettled in Birchtown, King honed his trade as a master carpenter and was also ordained as a Methodist minister. Unfortunately farming conditions in Nova Scotia were notoriously poor those years --in some instances bordering on outright famine-- and in 1792 the Kings decided to take advantage of a long-standing British offer to move to the newly-founded Province Of Freedom (later Sierra Leone), an established community for freed Blacks. The Kings were among the first (of approx. 1,200) settlers in what would become known as Freetown, although Violet died of malaria soon after they had arrived.

At the behest of the Sierra Leone Company, King was trained in London for two years as a teacher and missionary, and then returned to Freetown in 1796 to dust off his preaching skills --language barriers be damned. At some point during his time in London he penned his autobiography, Memoirs of the Life of Boston King, which would eventually see publication in serial form in 1798 in Wesleyan Methodist Magazine. The publication is significant because it was one of the very first written narratives of American slave life to see print --preceding Frederick Douglass's seminal work by nearly 50 years. At one point while in London King preached to a white congregation and reflected upon this in his memoir: "I found a more cordial love to the White People than I had ever experienced before. In the former part of my life I had suffered greatly from the cruelty and injustice of the Whites, which induced me to look upon them, in general, as our enmies (sic): And even after the Lord had manifested his forgiving mercy to me, I still felt at times an uneasy distrust and shyness toward them; but on that day the Lord removed all my prejudices."

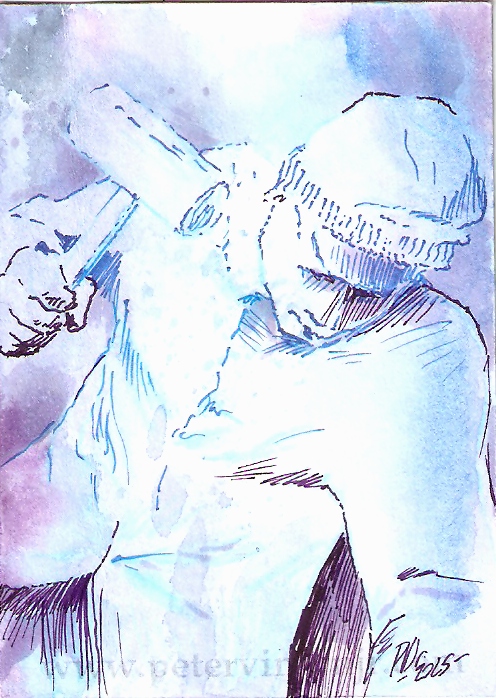

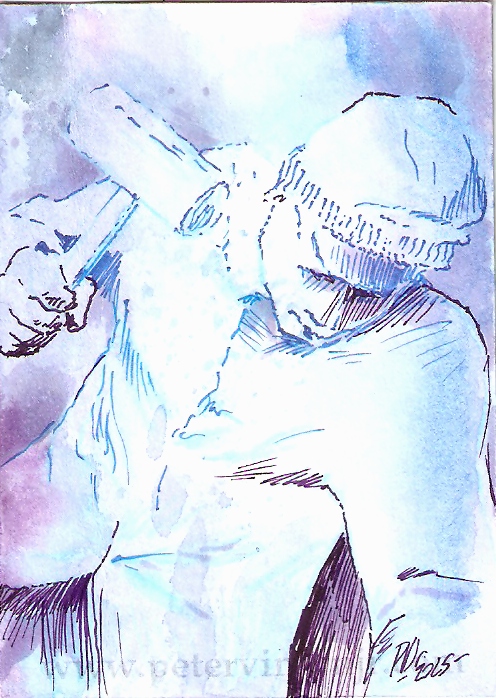

King married again in 1802 but his second wife, Peggy, also passed. His narrative continued to be republished in successive new editions, with the most recent iteration being The Life of Boston King, Black Loyalist, Minister, and Master Carpenter (2003). Once again bereft of any reliable period images, my illustration is instead based on a sculpture of King (artist unknown) that is part of a display at the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown.

Next lesson - Lesson 199: Lemuel Haynes

Return to www.petervintonjr.com Main Page

Now let's talk about an actual Black Loyalist. Meet Boston King, born enslaved in (or around) 1760 in South Carolina. Significantly, King's parents were first-generation slaves (meaning, kidnapped and brought over from Africa). Both were literate and ensured that their son would also become so. Ostensibly apprenticed as a carpenter, as King would later tell it, his particular owner was so harsh and cruel with his punishments (floggings) that one instance left him unable to work for three weeks. During the Revolution, King stole ("borrowed") a horse and slipped away from his owner, pledging loyalty to the British near Charleston, undertaking dangerous missions on behalf of Captain Grey of the New York Volunteers, which was a Loyalist regiment from Nova Scotia. King later made his way to New York --the last American port to be evacuated by the British-- and while there he met Violet, another former South Carolina slave who had also joined the British side with the promise of freedom. After the Revolution, Boston and Violet were given certificates of freedom for their service to the British crown. Along with nearly 3,000 other Black Loyalists who had risked severe punishment and even execution during the war, they were evacuated and resettled in British-held Birchtown, Nova Scotia.

Now let's talk about an actual Black Loyalist. Meet Boston King, born enslaved in (or around) 1760 in South Carolina. Significantly, King's parents were first-generation slaves (meaning, kidnapped and brought over from Africa). Both were literate and ensured that their son would also become so. Ostensibly apprenticed as a carpenter, as King would later tell it, his particular owner was so harsh and cruel with his punishments (floggings) that one instance left him unable to work for three weeks. During the Revolution, King stole ("borrowed") a horse and slipped away from his owner, pledging loyalty to the British near Charleston, undertaking dangerous missions on behalf of Captain Grey of the New York Volunteers, which was a Loyalist regiment from Nova Scotia. King later made his way to New York --the last American port to be evacuated by the British-- and while there he met Violet, another former South Carolina slave who had also joined the British side with the promise of freedom. After the Revolution, Boston and Violet were given certificates of freedom for their service to the British crown. Along with nearly 3,000 other Black Loyalists who had risked severe punishment and even execution during the war, they were evacuated and resettled in British-held Birchtown, Nova Scotia.